Speech to women who worked at the Magdalene Laundries

Áras an Uachtaráin, Tuesday, 5th June, 2018

Sabina and I warmly welcome you all here to Áras an Uachtaráin for what we regard as a most important occasion when so many former residents of the Magdalene laundries have gathered together from around Ireland and from around the world.

It is truly a great honour for me, as President of Ireland, and for Sabina to welcome you all to our home. I want to thank you, and those who are accompanying you, for taking the time to be with us this afternoon in Áras an Uachtaráin, the home of the President of Ireland, and, indeed, we hope that your making the decision to spend time together over these few days has the warmest possible outcome for you all.

It will, I know, be an opportunity for you to share your experiences with each other and perhaps, in some way, to continue to help us all as a society to understand our past, and help us all to heal and come into the light from the darkness of that past.

Many of you may not know each other. You worked in different Magdalene laundries at different times and the reasons you came to be in the laundries are, I know, varied. Some of you may have spent many years in the laundries and some much shorter periods. As women, you have gone on to live very different lives in different parts of the world. It is only to be expected that your lived experiences, your perspectives on your time in the laundries, and how you reacted to those experiences, will be as diverse as your lives are. The shared common experience of having lived and worked in a Magdalene Laundry, however, makes a bond that you share.

This afternoon Sabina and I know that we are welcoming a special group, 230 individual women, and each of you hold part of the story of the Magdalene Laundries. Since the foundation of the State, over 11,000 women spent time in the laundries, but their experiences were too often never shared.

A combination of stigma, shame and an unreceptive society condemned so many women to concealing their experiences, their trauma, their hurt. In recent years the silence has been broken and you all have helped to let the light into some very dark corners of our shared past. You have presented us with what makes a very harrowing and deeply uncomfortable reflection of an Ireland some would prefer not to be able to recognise, but which has to be acknowledged, transacted and to which a response must be made.

All of you and of all the other women who cannot be with us today were failed by these institutions, the experience of which you share, and the religious orders that ran them. You were profoundly failed by the State which, in its relationship to these institutions, should have had your welfare at its core. You were failed by Governments that knowingly relied on the existence and practices of these institutions rather than addressing your particular needs in other, more sympathetic ways. You were also failed by a society that actively colluded in your incarceration and treatment or chose to look the other way, averted their gaze, as vulnerable girls and women were subjected, in so many cases, to further abuse and degradation.

I know that many of you have engaged directly, or through some of the excellent representative groups, with the Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalene Laundries and with Justice Quirke in the construction of a redress scheme. Indeed, more recently, you have also worked with the Ombudsman in addressing deficiencies in that scheme. This has been vitally important, not only for you as individuals but also for Ireland as a nation, as we try to come to terms with, and face up to, our failings in the past.

Each of your individual experiences is a critical element of the whole, and all are equally important in enabling us to engage ethically with your stories and to truly understand them. It is only through this remembering and understanding that we can hope to learn and apply these lessons to our present and our future circumstances.

The treatment of vulnerable citizens in our industrial and reformatory schools, in the Magdalene Laundries and in Mother and Baby Homes represents a deep stain on Ireland’s past, a stain we can only regard today with great shame, profound regret and horror. It is sobering to consider that many women were also victims of the cruel and degrading regimes of Industrial or Reformatory Schools before being referred to the Laundries, and so many were intimidated into a silence by the abuse of authority of one kind or another.

Ireland failed you. When you were vulnerable and in need of the support of Irish society and its institutions, its authorities did not cherish you, protect you, respect your dignity or meet your needs and so many in the wider society colluded with their silence.

As a society, those with responsibility pretended not to know or chose not to know. The denial of all of this continued for many, many years until one by one you, the victims and survivors of that time, began to come forward, began to tell your stories, began to force Irish society and institutions who had conferred an immunity on themselves to look you in the eye and listen to your personal histories.

May I also pay tribute to all those who have initiated research tried to draw attention to your stories, break the silence, when these issues were receiving little attention elsewhere, and may indeed have been hidden. I think of writers such as Patricia Burke-Brogan, and Dr. Frances Finnegan, for example, but there were others too.

As you confronted contemporary Irish society with the legacy of a painful past and the question of how that legacy could be addressed, a long and difficult silence began to shatter and break. The stories Ireland was confronted with were harrowing, heart rending and deeply uncomfortable. They were stories of forced labour, of humiliation, of fear and sadness and of despair. They were stories of injustice; stories that continue to speak so loudly and so distressingly of indifference and cruelty fanned by ignorance, prejudice and intolerance, above all by an unquestioned authoritarianism.

You were apologised to by An Taoiseach, Enda Kenny in the Dáil in 2013 but as President of Ireland, I want to acknowledge again the wrong that has been done to you, the pain that has been caused in your lives and the opportunities that have been lost to you as a result of your mistreatment. Today, here in Áras an Uachtaráin as President of Ireland, mar Uachtarán na hÉireann, I apologise to you - survivors of the Magdalene regime.

Your individual tales, the personal narratives that lie behind the overall story of the Magdalene Laundries is what has brought you together here in Dublin. Tomorrow you will have the opportunity to recount your own unique memories and chapters of the Magdalene experiences, and that is so important. It is an acknowledgment of the value of your personal testimony, your personal pain, and recognition of the consequences that have ensued for each of you, as a woman, from the damage and harm that was perpetrated in the name of the Irish State.

They are stories that involve your time in the Magdalene Laundries but may also involve other painful periods of your life. They are stories that were told with pain across the years in homes here in Ireland, in the United Kingdom, the United States of America and elsewhere as each of you sought to move on and rebuild your lives. They are stories that were hidden and buried for too long, stories that were sometimes denied, distorted, deliberately forgotten and even erroneously justified by some in society who wished to embrace an accommodating amnesia and to turn away from that most unedifying version of ourselves.

They are stories which were held, first and foremost, in the hearts and minds of courageous and admirable women determined in going public that their experiences would claim their rightful place in the history of Ireland and in the memory of its people.

Today, in Ireland and across the world, an increasing body of research has focussed on the Magdalene Laundries. Oral history projects are taking place in University College Dublin and Waterford Institute of Technology and are recording the experiences of not only the women who were held in the Laundries, but their family members, and some of the nuns who managed them and other people who had frequent contact with the girls and women confined.

Researchers at UCD have also been developing videos and lesson plans for secondary school students in order to ensure that future generations will learn about, and take lessons from the Magdalene Laundries story. None of this could have happened without the women, of whom they will hear, including those of you gathered here this evening, who came forward to tell your stories.

Your stories confront an Ireland of the present, with the Ireland of closed doors and secrecy, one that wronged you; an Ireland where respectability often trumped compassion, where human rights were not respected, and could be casually withdrawn, from those deemed to have contravened what was defined as ‘respectable’ behaviour. Today we remember that dark chapter, and the version of Ireland that permitted it to unfold.

Today we also mark a new and positive turn on the long journey from darkness to light that has been undertaken by you personally over so many years, and by Ireland as a nation in more recent times. We have moved from a time of disbelief, denial and even hostility towards your experiences, to a time where we acknowledge that we must deliver compassion, listening and a genuine and heartfelt will to hear, to share and to learn from your testimonies.

You are Irish citizens who have been greatly hurt and wounded by the past experiences inflicted on you. But you are also women who refuse to be defined by such experience. I truly hope that the public addressing and redressing of the consequences of those experiences, and the commemorations that acknowledge the sufferings of so many thousands of women, will help to ease the burden of those past wrongs, a burden that some of your fellow citizens have striven to shoulder with you in recent years.

I also welcome you as inspiring and courageous women of whom we, as a country, are very proud indeed. Your generosity in sharing your difficult stories has allowed us to engage with the Magdalene Laundries story as an important episode from which hopefully we can draw wisdom, including the knowledge of the great harm that can be done when publics are not vigilant, when publics are cowed into not having the courage to question the status quo, when society fails to address institutional indifference or cruelty wherever it might arise.

I commend your resolve and your courage in facing your painful past. I pay tribute to you for your decision to share your experiences with each other. It put me in mind of the valuable role of the wounded healer to which Professor Michael Kearney, founder of the palliative care movement, has drawn so much attention. The wounded by listening to the wounded become the most powerful of healers. Most of all I thank you for helping Ireland and contemporary Irish people address a great wrong.

I realise that many of you left Ireland shortly after leaving the laundries and for some this might be your first time coming back. It is completely understandable that you would have turned your back on a country in which you were treated so badly. It would also be completely understandable for you to harbour resentment for the hurt you were caused.

I sincerely hope that the journey you have been on over recent years will help each of you in making peace with the past. Some of you may even have found it in yourself to forgive the individuals in the system that you encountered and that you were forced to endure.

Forgiveness can play a central and necessary part in healing. I acknowledge that it is very easy for me to say that. Some are asked to pay a very high price when they are called upon to forgive a great hurt that cannot be expelled from memory. Yet, the act of moving from ‘silent wounds’ to narrated words, as Richard Kearney puts it, is a powerfully healing journey. But in that journey too, you are the best judges as to the timing of the movement to ‘narrated words’, judges as to when it was too early, or as to when it might be too late, and the consequences of both.

I was in Belfast last week speaking about the peace process and encouraging a reflection on reconciliation between communities and between people who had inflicted and suffered such terrible acts. I quoted Bishop Desmond Tutu, an inspirational man who has written and spoken extensively on the issue of forgiveness, mostly in the context of the aftermath of the apartheid regime in South Africa. I thought when I was preparing to speak to you this evening, that his words might resonate with you and the ordeals you have been through.

He said:

‘Without forgiveness, we remain tethered to the person who harmed us. We are bound with chains of bitterness, tied together, trapped. Until we can forgive the person who harmed us, that person will hold the keys to our happiness; that person will be our jailor.

When we forgive, we take back control of our own fate and our feelings. We become our own liberators. Forgiveness, in other words, is the best form of self-interest. This is true both spiritually and scientifically. We don’t forgive to help the other person. We don’t forgive for others. We forgive for ourselves.’

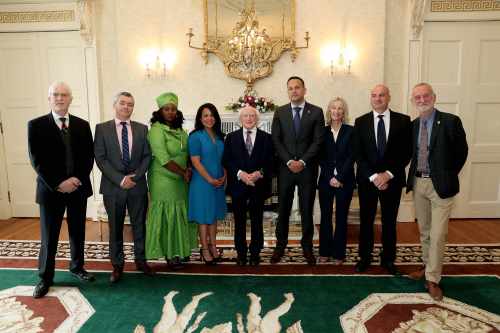

May I conclude by again thanking all of you for coming here today. May I thank Mary Kennedy for acting as MC for this event, May I thank the Hothouse Flowers who will play for us shortly, and finally, may I commend Minister for Justice Charlie Flanagan, Norah Casey and Dublin Honours Magdalenes for organising and hosting the two-day event that you will be attending.

Sabina and I are so very privileged that you have given us part of your time, and that you have come to our home, and we wish you all well.

Go raibh míle maith agaibh go léir.