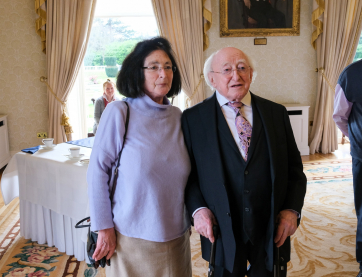

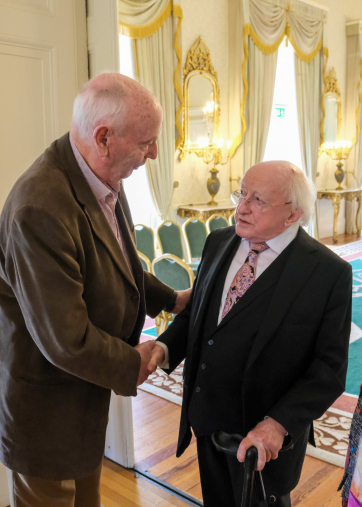

Speech at a Reception Hosting Members of the South-East Fermanagh Foundation

Áras an Uachtaráin, 6th March, 2025

A cháirde,

It is a great privilege to welcome today to Áras an Uachtaráin members of the South-East Fermanagh Foundation, representing, working and accompanied today by victims and family members of some of the most horrific acts of violence. I have in a number of speeches over the last 13 years spoken of the inappropriate, insufficient language in describing what was inflicted upon you.

Those of you here with us today have suffered unimaginable loss. In gathering here today, we remember formally all of the personal and public contributions made by each of your dearly loved relatives in their unique and individual lives, the difference they made and the legacy of service to the public and fellow citizens which they left in the lives of so many.

But in truth, yours is a recall that is beyond anybody else’s memory or words.

The memorial quilt that you brought today, which contains patches representing many of the victims of the conflict, including new patches recently sown to represent those victims who worked as members of the policing and security services. The quilt addresses intimacy, loss and memory in a way that words fail. It is a beautiful and moving piece of art, offering a gesture of understanding of the human price paid by individuals, families and communities such as yourselves who have been made victims by terrorism. I thank you for giving us the opportunity of exhibiting it here in Áras an Uachtaráin.

For over 25 years South-East Fermanagh Foundation has played, continues to play – and I wish it well in its work – such an important role in helping the large number of individuals who have had inflicted on them deeply traumatic experiences, providing practical and emotional support.

Since 1998, your Foundation has become a recognised provider of services for victims and survivors of terrorism. The Foundation’s role has evolved and expanded from its original geographical base in South-East Fermanagh with staff now located across Northern Ireland. The Foundation makes no distinction on the basis of religion or ethnicity.

That you have, over the past eight years, expanded your scope further to include the needs of victims and survivors based south of the border, thus ensuring all-island access to support services, is so welcome.

The research that you published recently, Terrorism Knows No Borders, which I would like to recognise today, constitutes that vital form of evidence known as “the lived experience”. It is a crucial medium for what I call the voices ‘from below’, voices often not heard, wilfully or otherwise; an opportunity for individuals and groups to give their own accounts of events from the past, painful as they may be, thereby becoming important agents of change in improving awareness and understanding. The consequences of what was experienced were not confined in time and peace and had life-changing impacts for the future.

County Fermanagh was witness to one of the most appalling acts of violence during the Northern Ireland conflict, the Enniskillen bombing on Remembrance Sunday, 8th November 1987. The explosion, which occurred during a ceremony honouring war veterans at the town’s cenotaph, claimed the lives of 11 civilians and injured scores more.

The Enniskillen bombing sent shockwaves through the community and the entire island, serving as a sombre reminder of the human cost of the ongoing conflict. The indiscriminate nature of the attack, which targeted a peaceful gathering of mostly older people, was widely condemned by all sides. It was no ordinary conflict, with indiscriminate killing serving murderous criminal intent.

The Enniskillen tragedy became a catalyst for change, as people from both the Catholic and Protestant communities united in their grief and their determination to prevent such atrocities from occurring again.

In the wake of the bombing, Enniskillen and County Fermanagh residents demonstrated a remarkable resilience, compassion, and unity. The resilience of the human spirit was exemplified when people from all backgrounds came together to support the victims’ families, attend funerals, and participate in community-led initiatives aimed at fostering peace and understanding.

That spirit of cooperation and shared purpose that emerged in Enniskillen inspired others across Northern Ireland to work towards ending the cycle of violence. There is, however, so much a distance to go in that regard.

The town’s experience demonstrated the power of grassroots efforts in the making of efforts at bridging divides and promoting understanding at a time when political progress seemed elusive.

That response to the tragedy, the wish for a commitment to peace and the rejection of sectarianism served as a beacon of hope and reconciliation amidst the darkness of the period. It suggested and exemplified that a brighter future was possible through dialogue, understanding, and a willingness to move forwards together.

Building upon this work, we must be willing to invest the necessary time and patience that is required to deal with the origins and consequences of violence. This includes having the courage to consider matters such as the importance of integrated education.

We are left with a horrific legacy by those years of violence on this island, including the thousands of people who lost their lives and the many more lives damaged in so many profound ways.

Today is an opportunity to remember all of those who died in the various campaigns of violence unleashed across those decades, tragic events that have torn families and communities apart and from which victims and victims’ families have been supported by South-East Fermanagh Foundation.

As I have noted, included within the death toll are of course members of the security forces from the three jurisdictions. May I take this opportunity to acknowledge those members and former members of the policing and security services from the United Kingdom and Ireland and their families, including those of you with us today, who bore witness to unspeakable horrors.

We recall too the many other members whose lives were so tragically cut short.

As difficult as these events are for us to recall, and particularly for those who suffered loss or injury and their families, amnesia on these events would constitute an amorality.

We must recall, in all of their richness of prospects and living, the lives of those who were taken from their families, recognising the loss felt by their families, their friends, and their communities, and the right of all such concerned to have these memories of their losses acknowledged, recalled, and given appropriate commemoration.

I commend all of those from across their communities who come together through the medium of community groups such as South-East Fermanagh Foundation, the many individuals who have reached out and found support across each of the too many decades over which the violence raged.

It is only through this path of coming together in recognition and sharing of each other’s experiences and losses, and by acknowledging the different narratives that emerged in recall of those decades, that we can best find an inclusive path to healing and ethical remembrance.

Since I took up office over 13 years ago, I have highlighted the need of engaging in the task of ethical remembering – the importance of including and recognising those voices that were, in our past, too often marginalised, disenfranchised or excluded – and of embracing narrative hospitality – a willingness to be open to the perspectives, stories, memories and pains of the ‘Other’.

In 2020, I launched Machnamh 100, hosting a series of seminars inviting reflections on the War of Independence, the Treaty Negotiations, the Civil War and Partition. Machnamh is an ancient Irish concept encompassing reflection, contemplation, meditation and thought.

It is my hope that these seminars – which brought together scholars from different backgrounds with an array of perspectives to share their insights on the context and events of that formative period of a century ago and on the nature of commemoration itself – may enable a deeper understanding of our complex, shared past so that we may build an emancipatory future together, at peace.

Your recently published research that we recognise today will also form a crucial part of that evidence base from which we may continue to promote understanding and healing.

The parties to the Good Friday Agreement expressed their belief that it was,

“essential to acknowledge and address the suffering of the victims of violence as a necessary element of reconciliation.”

That imperative remains as valid in 2025 as it was in 1998. It should be reiterated, and on an all-island basis we must take from your example.

Whether it is on this island or in other post-conflict locations across the globe, addressing the legacy of an embittered past is never, and can never be, an easy task. There is no simple formula of words or actions that can put things right. All societies emerging out of conflict wrestle with unavoidable pain, the legacy of the past and the measures required to address it.

For example, ‘reconciliation’ as a word is a powerful ideal, but let us now never make it an abstraction. It does not replace the loss of a loved one.

Words and language are so important. When addressing issues concerning victims and survivors, the word “closure” is one that sometimes is used. It is a word with which I have difficulty.

That any possible outcome to your struggle could grant you complete closure or totally heal the wounds of the grievous hurt that was inflicted upon you and your beloved family and friends would be a naïve suggestion.

Perhaps, however, as you continue on your journey, difficult and painful as it is, it may be possible, through the support that groups such as South-East Fermanagh Foundation offer, to learn collectively how to find resilience and survive and, as you help each other in mutual support and solidarity, you may become better and stronger survivors.

That in itself constitutes an extraordinary achievement, one that demonstrates the power of the human spirit to overcome adversity and rise above the natural inclination towards bitterness and understandable anger so that a path towards healing may become evident.

I take this opportunity, if I may, to offer my thoughts of respect and solidarity to all those who continue to struggle with the memories of all that they suffered over those years, and I wish them the deepest strength, as they go forward together in building a better shared future.

May I thank so many of those present for the strong voice which you have provided in your accounts and interviews, on behalf not just of your loved ones, but also on behalf of all those who have wished over the decades for a peaceful and harmonious future.

So many of you have spoken with such grace and passion against violence and helped bring the peace which we now must treasure and seek to build upon.

May I also recognise those of you present, and other members of your families not present, who I know have honoured the memories of your lost loved ones in following them into careers in public service, and the work that you have done and continue to do on behalf of people across the island.

As we continue on the road of peace towards a better future, we must not ever forget all those who died, those who mourn them and those who were injured. We must be willing to encourage and require of each other to do more in recognising and addressing the needs and requirements for justice of victims and survivors.

Let us take the opportunity today to reaffirm not only our commitment to peace, and our revulsion of war and conflict, but our ongoing support for relatives and surviving victims who, while many continue to suffer, benefit from the tremendous work that your Foundation and other support groups continue to provide.

Síochán sioraí le hanamacha na marbh. Mo bhuíochas libh uilig as éisteacht agus bheith i láthair.

Beir beannacht.