Keynote address at Vietnam National University

Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Tuesday 8 November 2016

President of Vietnam National University,

Dr. Nguyen Kim Son,

Excellencies,

Dear Students,

Friends,

It is my great pleasure to be here with you all in Hanoi, this ancient city of culture, and the vibrant capital of a friendly nation. I am honoured to be the first Irish President to pay a State Visit to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and I hope that my visit will contribute to sustaining and deepening the true and growing friendship that unites the peoples of Ireland and Vietnam.

I thank you all for the warmth of your welcome to Hanoi and to Vietnam. May I also extend my sincere thanks to President Son for his invitation to address the student and academic body of this prestigious University on a theme which is central to my visit to Vietnam, and to our nations’ common future on this fragile planet – that of Sustainable Development.

I am pleased to see gathered here this morning representatives from other educational institutions, alongside representatives from a range of national and international organisations, youth groups, non-governmental organisations, and policy analysts. All of you will have an integral part to play in crafting the new forms of international cooperation, diplomacy, economic and social policy that are required so as to respond adequately to both the great possibilities and the risks of fragmentation which the latest technological revolutions and new balance of trade and political uncertainties have opened up in our global relationships.

You are crucial participants in the conversation arising from all quarters of the world about the pressing need for new models of development that are based on diversity and on ethical purpose. Most of you here are students, for whom many futures are possible, in an ever-more interdependent world for which a pluralist scholarship is essential. You are invited to contribute to imagining and shaping a new form of globalisation appropriate for your generation and its future – one that can foster cohesion, social progress and a balanced relation between our human species and nature in all its forms.

This year, Ireland and Vietnam celebrate 20 years of diplomatic relations. However young the formal relationship between our two countries may be, it is one that is built on the solid bedrock of mutual esteem and authentic understanding.

There is so much shared experience in our respective histories; there are so many ways in which we Irish, when we acquaint ourselves with the history of Vietnam, can identify, in sympathy and imagination, with the aspirations of the Vietnamese people. Ireland’s national journey and the journey of Vietnam are ones that chime: in your recollections we hear echoes of our own path. Yours is a history of so much inflicted suffering by external powers, that while it must not disable your present, or deprive you of future possibilities, yet it would be so important for you never to be asked to assume some false amnesia in its regard. Your history in its fullness belongs to you and the world must learn from its imposed tragedies.

Both our cultures have their roots in ancient civilisations renowned for the value they placed on scholarly learning, spiritual cultivation and the arts. Both our peoples have endured the harmful experience of colonisation, and, in your case, the ambitions of four imperialisms. Both have suffered from the scourge of famine – “the terror of the hungry grass”, as Irish poet Donagh MacDonagh described it. Both of our nations have suffered, in cultural terms, from imperialist theories of culture which sought to justify the racial superiority of the coloniser over the colonised, and to rationalise the ruling of the world by a handful of imperial powers.

We recall the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, after that collision of Empires that was the First World War: a conference to which a young Ho Chi Minh sent a petition asking for the delivery of the independence that had been promised from France. He did not receive an answer from the presiding world powers. Similarly, the doors in Paris remained closed to the delegation of Irish Republicans who travelled there in an attempt to garner support for the cause of independence from the British Empire. Both rejections were perceived by the Irish and Vietnamese leaders of the time as proof of the risks of placing trust in concessions from an imperial power.

It is important to remember that the Paris Conference was unfolding just a few short years after the Easter Rising of 1916, when a few thousand brave men and women rose to defy the power of the British Empire. This was a milestone event on the path to Irish independence, an event of which we, in Ireland, are celebrating the centenary this year. And we do so with what I have called a hospitality of narratives.

Both our peoples have led an unyielding and irrepressible struggle for independence. We both know, too, how difficult it can be to secure, vindicate and deliver on the promises of freedom, justice and equality that motivated the struggle for independence in the first place. The decades following the heady atmosphere of the days of declared independence are the most challenging.

In recent decades, our two countries have undertaken a challenging, but rewarding, journey from conflict to fruitful and harmonious relations with those who are the successors of our oppressors of the past. In economic terms too, both Ireland and Vietnam have rapidly moved from being low income agricultural societies to diversifying their production and achieving significant social and economic advances in a complex, globalised world, that is ever more interdependent, and not only in trade, and that now needs a new and imaginative international architecture in an institutional sense, if it is to achieve a diversified democratic future.

With rapid changes and new opportunities have also come tremendous new challenges. The globalised economic and trade structures to which Vietnam and Ireland have been opening, and in which they have been participating ever more actively and with success in recent times, are ones that create great hopes, suggest great opportunities for increased prosperity, security and social progress, but also ones that involve risk and serious challenges. Everywhere in our global system we can see how deepening inequality is threatening social cohesion, and how inter-generational justice is threatened as we witness our natural environment degrading at an alarming pace.

We should reflect deeply on the opportunities and the risks before us, risks that we share. No nation should ever be made to rush unthinkingly towards a model of development presented in the illusory guise of an ill-defined modernity. Is the modernity on offer simply an invitation to imitate the practice of others? Are current models of global trade and finance, production, extraction of resources, ones that truly advance the fundamental objective of human development?

Do those models protect the hierarchy of purpose that should exist – that must be restored – between morally purposive economic and social outcomes? As to quantifying our achievements or failures: To what extent do growth rates as we currently define and measure them reflect the ability of our economies to respond to the basic needs of our most vulnerable citizens?

These are questions we must answer, yes, through the prism of our current circumstances, but now also within the new parameters of the global agreements that were secured in 2015 in relation to sustainable development and climate change.

The scale of the global challenges we face together requires, it is my deep conviction, not only a recovery of the genuinely idealistic impulses which drew our forefathers forward in their best and selfless moments towards a new world of independence. It also requires, of all of us and you now, new models, new paradigms for cooperation at national and international level, and also new scholarship, of such a nature as can generate balanced and respectful relationships between the peoples of the world, and between humans and the forms of life on their shared planet.

As places of learning, universities and institutes of technology have a crucial role to play in our transformational tasks, and we must ‘think long’. As Vietnam’s much respected leader, Ho Chi Minh, once said:

“For the sake of ten years, we must plant trees, for the sake of one hundred years, we should cultivate people.”

As a former University teacher, it is always a pleasure to return to a University setting, and I am particularly delighted to have this occasion to meet students of Vietnam National University, renowned for the high quality of its academic programmes. It is indeed a privilege to be here with you today in an institution that will produce the next generation of thinkers, policy makers, analysts and artists – and great concerned human beings.

All of you students are, as I was, so fortunate to be able to dedicate several years of your life to learning, to intellectual work, to reading and reflection. So many, and particularly those not as fortunate, rely on you to make the most of this special time in your lives by seeking to think creatively, imagining a bold new world, one very different from that which has so tragically squandered so much of the possibilities of science and human intelligence in war and anticipation of war. Generations that have failed to eliminate global poverty, claimed hegemony for industrial systems that have come to threaten the future of the planet itself, through the degradation of our natural resources.

My wish for you in Vietnam is the same as my wish for Irish students – that you will experience the necessary pluralism of scholarship and teaching as will enable you to grow into critical, thoughtful and imaginative citizens with courage. My wish is that you will, through your studies, through your exchanges with others, develop the capacity to define modernity anew, in an inclusive, reflexive, ethical and ecologically responsible way.

My wish for you, in other words, is that you will imagine and give reality to models of development, that, while retaining the best of universal developments in science and technology, will also be rooted in your culture and in your history, making space for intuitive wisdom as much as rational applied thought. I hope that your knowledge will be of a holistic, life-enhancing kind, rather than simply narrowly utilitarian. My wish for you is that all those skills you are cultivating during your studies – skills of patience, clarity in reasoning, persistence, but also gifts of imagination and creativity, the values you rely on for the stuff of your dreams – will remain with you both in your personal journeys and in your collective endeavours.

On Sunday, I had the opportunity to visit the Van Mieu Temple of Literature. One could not be but moved by the thousand-year long tradition of scholarly learning embodied in that beautiful place. Such ancient traditions – which recall for us a time when intellectual activity was rooted in ethical practice, when the world of man and the world of nature were grasped in harmony – are ones that have lost nothing of their relevance as we face the challenges of the 21st century. Indeed, I profoundly believe that our ability to respond adequately to those challenges hinges upon our ability to achieve a historic reconciliation between ethics, ecology and economics. The order we must pursue must be an open, inclusive, and democratic one that serves the needs of a global community rather than any empire or contending order of elite powers.

The Vietnam National University (VNU), as the oldest university in Vietnam – celebrating the 110th anniversary of its founding this year – is both a custodian of the values enshrined by the ancient scholarship and the location for an exploration of the uncharted waters, the new horizons, of the new century.

I know that the Vietnam National University plays a special role in education in Vietnam, in particular through the central part it has played in building international partnerships with educational institutions abroad. We rely on such partnerships of intelligence, cooperation of minds, exchanges of ideas and sharing of knowledge, if we are to respond to the challenges we face together in relation to climate change, to medicine and to human health, to food security, and to so many other important spheres of human life.

All our efforts will benefit from international co-operation, and in that regard I am, as President of Ireland, extremely pleased to note the developing links between Vietnam National University and Irish Universities, in particular, University College Cork and Trinity College Dublin.

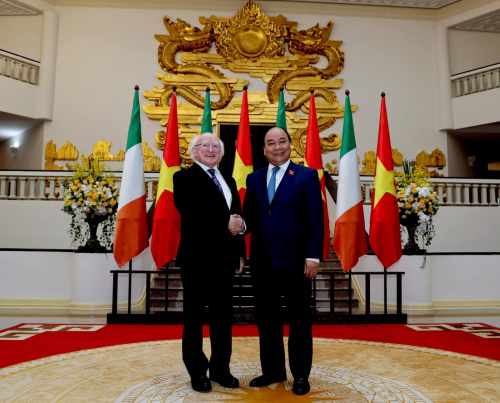

Yesterday at the Presidential Palace, I witnessed alongside

President Tran Dai Quang the renewal of the Memorandum of Understanding between Ireland and Vietnam on Co-operation in Higher Education. This renewal will deepen even further the excellent cooperation that already exists between our universities, and which has seen over 100 talented Vietnamese graduates being supported by Irish Aid to undertake postgraduate studies in Ireland. I have had the pleasure of meeting a number of these scholars in Ireland and I was impressed by the depth of their commitment to scholarship and to using their new skills and expertise to positively contribute to the development of Vietnam.

I hope that Irish Aid’s new pilot programme, launched this year with the aim of strengthening long-term research and exchange links between Irish and Vietnamese universities will yield equally positive results. I am delighted that the President of University College Cork (UCC), Dr. Michael Murphy, is among those representatives of Centres of Higher Education accompanying me on this State Visit.

Vietnam National University’s Department of Social Sciences and Humanities has entered into a partnership with University College Cork to develop undergraduate and postgraduate programmes on rural development. This issue of sustainable rural development is one of very acute importance in Ireland too, where the number of family farms has been dwindling at an alarming pace over the last half of a century.

The challenge of having a sustainable, productive, transparent with full tracability, agricultural sector is one in which we have made tremendous achievements, but we share with you the greater challenge of finding appropriate ways of supporting our rural communities in the long-term. I know that in Vietnam – and, in particular, in your country’s mountainous areas – you have recognised from your own studies that too many farming families still live in poverty and I wish you the very best in all that you do to address that problem.

I hope that we will, in years to come, witness many more constructive educational partnerships between Ireland and Vietnam, and at every level, partnerships that will be mutually beneficial, partnerships that will invite the brightest young people in our societies to put their intelligence and creativity in the service of the collective objectives of sustainable development for all.

However great the global challenges we are facing may be, we can, in this century, if we set about it collectively and creatively, succeed in delivering the promise of sustainable development. Doing so is not some vague utopia, rather it will be immensely rewarding to see the fruits of one’s intellectual work delivered for the welfare of all.

It is a promise on which we must deliver urgently. Failure in relation to either of the interrelated challenges of sustainable development and climate change would be a disaster. It will result in the destruction of the prospects of millions to live a life of dignity. Given our existing demographic projections, it will result in massive migratory flows, from poverty-stricken areas, first to cities that are unprepared, then on into the uncertainty of international migratory trails, to which we are currently making such a dismal response.

I am pleased to say that the two milestone agreements signed last year, at the Climate Conference in Paris in December, and at the Conference on the new Sustainable Development Goals in New York in September, give us good grounds for hope, reason to believe, that concern is shared, that success is possible – is achievable – that we can succeed in rolling back the plights of extreme poverty, hunger, enforced mass migration, that we can better anticipate conflicts and address environmental degradation.

Taken together, those two, interrelated, frameworks for international action on climate change and on sustainable development constitute the most ambitious global agenda the nations of the world have ever set themselves. We are now all called forth to rise to the challenge of implementing what is an Agenda of Hope.

Yes, it is true that the Agreement signed at the Paris Climate Conference, the so-called COP21, has left a number of issues yet to be resolved. However, I believe that we can all agree that COP21 is a very significant achievement when viewed through the lens of the disappointing failures of the past. It truly represents a turning point in the international response to the climate crisis.

We now have almost universally agreed scientific indicators. We have an agreed framework for collective action. The climate justice movement is becoming global. Many of our citizens have already started to change their consumption patterns and ways of life; thousands of cities, provinces and regions around the world have committed to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions.

We are, however slowly, entering a new era: the era of low carbon, with new geopolitical balances in sight, and huge economic and environmental opportunities for all countries, including the poorer ones, to use energy more efficiently and to take advantage of the availability of new technologies to enhance their capacities in the areas of wind, solar, and other forms of renewable energy.

As we speak, the latest international conference on Climate, COP22, following up from last year’s COP21 in Paris, is underway in Marrakech. The targets and objectives brought to that conference by our governments must not be couched in abstract figures. These conferences must never be construed as abstract exercises in diplomatic skill. The fight against climate change is one that cannot any longer be postponed. It is an issue on which we now have near full agreement as to the scientific facts. The urgency of our position has been made clear and, of course, we must be aware of our immense responsibility towards future generations.

The choices we are making in this generation will determine the fate of millions of our fellow global citizens in future generations.

What is our present position?

Issues of poverty, hunger, migration, of development and climate change are inextricably connected. Recent years have shown that the food security and livelihoods of countless men, women and children are seriously undermined by rises in sea levels and the dramatic increase in the frequency and severity of rainfall, floods and droughts. What is at stake is not just the livelihoods of this generation, but also the future of future generations, and, even, the future of life itself on our shared planet.

Here in Vietnam, and in the Mekong Delta Region, the destructive effects of climate change have become a lived reality for many citizens. In preparing for this State Visit, I was shocked to learn how, over the past 50 years, the average temperature in Vietnam has increased by approximately 0.5°C and the sea level has risen by about 20cm. Furthermore, Vietnam’s location in the tropical cyclone belt leaves it particularly vulnerable to natural disasters – disasters that tend to affect disproportionately the poorest rural communities. The torrential rain and heavy flooding witnessed by regions of central Vietnam last month is again a recent example of the urgency of our fight, which must be a collective fight, against climate change.

In our international meetings, we must never be slow to acknowledge that the victims of climate change were, in so many cases, neither the authors nor the beneficiaries of the industrial and extraction practices that produced, and provoked, the problem of climate change and pushed it to its present threatening level.

The two challenges of climate change and sustainable development are, as I have said, intrinsically interconnected. It is becoming increasingly obvious that the effects of extreme weather events threaten the effective delivery of a range of basic human rights, such as the right to safe water and food, the right to health and adequate housing. For example, in those states that are, or have on their territory, vulnerable small islands, the threat is even more acute and the consequences more severe, as was made so clear to me when I met the representatives of the Marshall Islands last year in Paris.

Dear Friends,

You, in your generation, have to succeed where mine and previous generations have failed.

The work of responding to extreme poverty remains, everywhere, unfinished business. Globally more than 800 million people are still living in extreme poverty. Yes, the Millennium Development Goals, which preceded the Sustainable Development Goals, resulted in an overall reduction in poverty at global level, but nearly a billion of our citizens still remain unrelieved, stuck at the bottom of an unequal global system.

Indeed, the achievement of the Millennium Development Goal was uneven. In China, Brazil and Vietnam, countries which all had state-led anti-poverty strategies, the achievement is very impressive. There are inescapable lessons for the achievement of the Sustainable Development and Climate Change goals in that fact. The role of state-led initiatives was crucial where success was achieved. Rising global levels of inequality, poverty, hunger, are also not unrelated to the diminished role of the State. In the context of the largely unregulated, financialised model of economic governance which has gained ground globally over the last four decades it is important that we not week to avoid or evade these facts of our recent history. An avatar of such recent models is, for example, the escalating amount of hedge funds-controlled future derivatives in basic foodstuffs, which constitutes such a threat for the food security of the poorest peoples.

Here in Vietnam, you have made huge strides towards the eradication of poverty. While about 70% of the Vietnamese population lived in extreme poverty by the end of the war, those figures have been reduced by more than half over the next quarter of a century. Over that period of time, the Vietnamese government has also managed to build up a network of primary and secondary schools in most communities, as well as a basic structure of healthcare across the country. Electricity is now available to almost all households and access to clean water and modern sanitation has risen from less than 50% of all households to more than 75%. These are real achievements. They constitute a shared social wealth.

Ireland has been proud to support in a modest way such achievements ever since we opened an embassy here in Hanoi, eleven years ago. In the intervening time, Ireland and Vietnam have built a very positive development cooperation partnership, centred, in particular, on the objective of reducing poverty among ethnic minority groups in Vietnam’s mountainous areas. Working together, we have sought to help, by focusing on inclusive, community-based development action that benefits, in particular, Disabled Persons Groups, Community Development Organisations and the Lesbian, Gay and Transgender communities. Such efforts we hope encourages and assists the development of an inclusive, participatory civil society.

The international community also faces the difficult and most urgent challenge of preventing human trafficking. This terrible plight of human trafficking affects countless numbers of men, women and children, who are often seeking to make better lives for themselves and fall prey to ruthless criminals.

The factors which contribute to this problem are, like most of the global issues we face today, very often complex, and while difficult to resolve, must be tackled. Extreme poverty and migration from rural areas are primary factors, but we also need to consider carefully the impact which major development projects – such as the building of dams or the development of certain industries – can have on rural communities and on the continuation of their traditional livelihoods. We must be open to seeing how displacement occurs.

As Governments and as donors, we must be aware that our efforts to improve the lives of our citizens through socio-economic development can have unintended social consequences. It is critical that we assess our policies, our development programmes, and our engagement with the private sector, to mitigate any consequences that might generate human misery and suffering.

It is imperative that we plan ahead, so that citizens, and particularly the most vulnerable amongst them, are enabled to adapt – in dignity, without being forced to sacrifice the traditions and livelihoods to which they are attached – to a changing environment which sees some old models of work coming under pressure, and farmland giving way to infrastructure development. We must firmly and actively ensure that all of the men, women and children who are affected with such change are given access to the necessary tools for adjustment, including education and training, so as they are enabled to remain the dignified authors of their lives, and not the targets or victims of change.

The problem of human trafficking requires a comprehensive response at the national level, but also a concerted international response, through bilateral as well as regional and multilateral initiatives. Like Vietnam, Ireland has engaged with the UN, with our partners in the EU, with you and with your counterparts in ASEAN, to explore how we might best address this grave issue. Ireland also actively supports the work of the International Organisation on Migration, and at regional level, the efforts of the International Labour Organisation to combat forced labour in Asia.

At the national level, domestic legal frameworks are key to combating forced migration and human trafficking. Both Ireland and Vietnam have ratified the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime and acceded to the “Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children”. Both our countries have also published national strategies to combat human trafficking.

Ireland is committed to continuing its support for the Vietnamese Government’s efforts to reduce poverty, particularly among ethnic minority communities, who are, sadly, suffering from acute levels of poverty and hence especially vulnerable to human trafficking. Ireland’s development cooperation in Vietnam includes support to develop small-scale investment in local communities, to improve their access to services and markets. We are, for example, providing support to a “good practice model” in Ha Giang Province that aims at ensuring that poor ethnic minority girls stay in secondary school, which education makes them less vulnerable to migration and trafficking.

Dear Friends,

Dear Students,

However great the challenges of global economies, international trade, unaccountable speculative flows, and development itself may be, today Ireland and Vietnam have emerged as countries on a path to greater prosperity, with a myriad of opportunities in sight for new international partnerships. It is now more important than ever that our two countries firmly embrace the principles of sustainable development. Now more than ever the three pillars of sustainable development matter: social, economic and environmental considerations must be equally central to our planning for the future.

I know that former Vietnamese President Sang attended the Climate Summit in Paris last year, and I was also very heartened to hear that sustainability, and the need to build up resilience to climate challenges, had been identified as a key priority by the Vietnamese government. I congratulate the Vietnamese people and their Government on such a positive response.

Your government has played a very constructive part in contributing to the definition of the new framework for global development upon which the nations of the world have agreed last year at the UN headquarters in New York. I want too, in this regard, to so heartily agree with words of the incoming UN Secretary General António Guterres, when he said that:

“We need to look towards the Sustainable Development Goals to provide a roadmap for the future."

Ireland is both proud and honoured to have had the great responsibility of co-chairing, together with Kenya, the negotiation process for this new global Agenda, known as “Agenda 2030.”

What distinguishes the new Sustainable Development Goals of Agenda 2030 from their predecessors, the Millennium Development Goals, is the universality in their scope. Indeed, as I hope I have already stated clearly in this speech, sustainable development is not simply a matter for the so-called “developing nations” of the “global South”, such as Vietnam. Sustainable Development – the possibility of flourishing in one’s community and culture and to enable future generations to do so too – this is an equally important challenge for those countries that belong to the so-called “West”.

Basic human rights such as the right to safe water and food, the right to health and adequate housing, as well as dignity, freedom from fear, and gender equality – these are core, universal values that are valid for, and must be vindicated in, any society across the globe.

Significantly, the 2030Agenda invites us to go beyond previous dichotomies in public discourse between ‘North’ and ‘South’ – discourses which, were reduced to rhetorical flourishes with their broken promises, a discourse that lost so many opportunities and broke the heart of such as Julius Nyerere.

After all, we have, today, in the so-called ‘North’, levels of poverty, inequality unemployment and exclusion that point to the existence of ‘a South in the North’. Then too, so many features associated with the industrialised ‘North’ have migrated to the ‘South’ – for example the phenomenon of privileged elites cornering the benefits of growth at the cost of the people in general. Thus all of us are invited to partake in a new and urgent conversation on the common challenges that face all of our nations in this new century – a new conversation that is about little less than the future of humanity itself on our shared planet, a new ethical, globalised economic order that turns the Agreements of Paris and New York into realities.

The 2030 Agenda is also significant in that it puts forward a holistic approach to development, emphasising – I quote – that “there can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development”. This is so important: for the first time at multilateral level, peace, political stability, accountability and good government are recognised, together with the economic, social and environmental pillars, as a virtual fourth pillar of development policy.

I should also take this opportunity, here in Vietnam National University, to emphasise the importance of Goal number 5, which proclaims the need to

“achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”.

Indeed, gender equality is a principle that should infuse all our thinking, not only on development, but in every area of policy. It is an issue that has gained new urgency as we witness, in several regions of the world, an appalling resurgence of violence against women and girls, often rooted in a hideous ideology of female inferiority.

Ireland and Vietnam are two nations that share an equally firm commitment to defending the equality and dignity of our women citizens. We are two nations who know what they owe, including in the moments of their struggle for independence, to the courageous women from their past. We are reminded, for example, of the Trung sisters, who, in 40AD, led the Vietnamese people’s struggle against the army of Ma Yuan. As one Vietnamese poem from the 15th century put it:

“All the heroes bowed their heads in submission. Only the two sisters proudly stood up to avenge the country.”

The life of the Trung sisters echoes, across the centuries, the courageous deeds of another pair of sisters, the Gore-Booth sisters, from the West of Ireland, who played a prominent role in the Revolution which stirred Ireland at the turn of the last century. The elder, Constance, was one of the military leaders of the insurrection of 1916, while the younger one, Eva, a pacifist at heart, was instrumental in organising the women’s trade union and suffragist movement in Britain, where she lived for most of her life.

Some of you here this morning may have seen the compelling exhibition organised by the Irish Embassy at the Vietnam Women’s Museum, to mark the anniversary of Ireland’s 1916 Rebellion. Highlighting as it did the central part played by women in Ireland’s struggle for freedom, I have no doubt that this exhibition found a strong resonance with those who viewed it here in Hanoi, the capital of a State in whose liberation and evolution so many brave women played – and continue to play – a crucial role.

It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Vietnamese Government is so committed to the promotion of gender equality. In addition to the guarantees enshrined in your Constitution, I know that milestone legislative measures which we must all welcome, were recently introduced to strengthen the position of women in Vietnamese society, such as the 2006 Law on Gender Equality and the 2007 Law on the Prevention and Control of Domestic Violence. These legislative initiatives I am sure will be welcomed by the Vietnamese people of all generations.

Of course, as with all spheres of equality, gender equality is, here in Vietnam, as well as in Ireland and everywhere in the world, an incomplete project. We must always be mindful not to lose sight of the fundamental importance of reaching gender equality in all aspects of our lives – our lives as political representatives, as citizens, as students, as workers and as educators.

This centrality of the values of justice, equality and dignity to our daily lives leads me to another point – that of who must take ownership of the implementation of our common sustainable development goals. Agenda 2030 is not simply a crucially important dimension of government policy and multilateral negotiation. It is a challenge of which each and every one of us, as citizens, must take ownership, in the way we shape our lifestyles, and deliver our abilities in intellectual, political and associative engagements.

For the deep change we so urgently need to take place at global level, it is indeed essential that all those concerned – national governments, civil society organisations, academia, business and citizens, play an active role in the achievement of Agenda 2030, just as they played a crucial role in its definition.

Parliaments and citizens across the world must not avert their gaze, or ever be encouraged to do so, when it comes to the implementation of this globally agreed Agenda. They must ensure that strategies on sustainable development are translated into clear and specific national priorities, action plans, responsibilities and budgets. Citizens must also be able and willing to hold governments to account to ensure that decisions are truly based on the needs of the people, including those who are marginalised and most vulnerable, our brothers and sisters in the human family.

That, of course, may be easier than holding some multi-national corporations to account. Yet, it must be done. We cannot allow ourselves to be intimidated by threats from powerful corporate interests such as, for example, those who put millions of tons of poison into the waters of Ecuador and who, when brought to account, went on to say that they would fight the fine imposed, as they put it “until hell freezes over... and then [would] fight it out on the ice”. We must have accountability, support for international law, and if that requires reforming the UN, let’s set about it.

We are all co-responsible, dear friends, in contributing to creating the right atmosphere for the wide-ranging transformation we need – the atmosphere of a new moment in global relations as can yield an integrated, culturally sensitive and environmentally sound version of development; an atmosphere as will invite all of us to be courageous in taking charge of change. We must keep the momentum going and retain the public interest in these issues.

Here in Vietnam, the energy and enthusiasm with which the government and the people have embraced the new Agenda 2030 is heartening, and encouraging – and it is an example to others.

As is the case in Ireland, and indeed everywhere else for that matter, it is important that all ministries, as well as provincial and local government, are fully engaged in the process of planning and implementation. Indeed, our own experience in Ireland tells us that a “whole of government” and “whole of society” approach are key drivers to the success of wide-ranging transformative agenda.

Of course, real progress on any of the 17 Goals agreed in New York is also predicated upon the international community’s ability to secure appropriate levels of funding – with the UN and the World Bank having estimated that the cost of global implementation of the SDGs is trillions rather than billions.

As we look at new ways of financing development, I strongly believe that it is imperative that we keep the issue of debt restructuring at the centre of our discussions. Indeed, the unsustainable debt position of so many countries, rich and poor, gravely undermines their capacity to plan and execute long-term sustainable development programmes. No serious or plausible agreement on development can ignore debt management issues, and more particularly, may I state very clearly, the central question of the role of the state and its financial capacity. States must be allowed the space to implement the new agenda. That may require dealing with the related issue of global debt restructuring.

Indeed, while it is important to explore innovative financing options and the role of the private sector in funding development, the state and its agencies will undoubtedly have a pivotal role in ensuring the long vision and inclusive approach that is necessary for the delivery of development policies that can benefit all citizens.

The problems posed by the financialisation of the global economy to which I have just referenced have been identified by a multitude of distinguished scholars and analysts, who have convincingly highlighted the correlation between the current, financialised version of the global economy we live with and the growth of inequalities worldwide.

The current – eight to one – ratio of unaccountable speculative capital to capital used for productive purposes is one that threatens our ability to effectively provide globally for the implementation of Agenda 2030. Achieving Agenda 2030 requires, may I suggest, the diverting of the ever-widening river of speculative financial capital towards the real economy and the creation of sustainable employment and investment.

The growing influence of respected dissenting voices, to the current structure of globalised capital flows, including that of Pope Francis, indicates, perhaps, that the hegemonic days of strident neo-liberal economics, that advocate a version of the market free of state regulation and extended to every sphere of life – that those days, then, might be coming to an end. The detritus of such ideological extremes is all around the global society, and I very much welcome the fact that, after many decades, the role of the State is again being re-examined and recognised as a vital one in responding to both existing and emerging global challenges.

There are, then, many encouraging signs that a radical rethinking of our economic models is underway, pointing to the need to control international finance. We see, too, suggestions for alternative measurements of growth emerging in such institutions as the UNDP and The World Bank. There is undoubtedly a new, multi-polar world in the throes of emergence. The opportunities are real to depart from the failed models of development from the past, in order to deliver new models – models that are rooted in an ethical consciousness, seeking to build on the inescapable solidarity which can bind together all societies across the globe.

Those new models in the throes of emergence will not, however, become reality without a profound renovation of our multilateral system. The United Nations, as an institution, will have a crucial role to play in efficiently supporting, coordinating and monitoring the implementation of Agenda 2030 at international level. More broadly, we need a new architecture of legitimate and well-resourced multilateral institutions – with consensual policies that are based on good and pluralist scholarship, an ability to translate agreed principles into action, but also genuine representativeness.

Even small steps are important. I welcome, for example, recent efforts in the World Bank Group to increase the voice and representation of so-called developing and transition countries (DTCs) within the Bank, but so much more remains to be done to create an appropriate framework for the governance of macroeconomic and financial policies in our interconnected world.

Finally, but so importantly, may I say how crucial the United Nations’ work on disarmament and non-proliferation of weapons is. This is an area in which Ireland and Vietnam are aligned and actively engaged. It is work that is critical for a safer and more secure world.

There is no doubt that political leadership is fundamental to the achievement of such critical global objectives. I am very confident that the incoming UN Secretary General António Guterres, with his exceptional experience of the work of the UN on the ground, will continue the good work of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon in leading the world onto a more sustainable path.

Dear Students,

A Chairde Gael,

Dear Friends,

May I emphasise again that eradicating the poverty and its associated suffering which undermines the lives of so many men, women and children on our planet is the greatest moral challenge we, as a global community, face. It is a challenge that, I repeat, we have not met with an adequacy of mind and heart in previous generations.

The scale of the change required, in both policy and mind-set, should not lead anybody to feel overwhelmed or powerless. Our new international agreements on climate change and sustainable development are global in their reach and in their demands; they ask us to meet the challenge by delivering a global consciousness and globally responsible actions. This scale and ambition of the 2030 Agenda should serve, not to intimidate us, but to inspire us – and I believe that in all of this, there is room to learn from the deep and growing friendship, the co-operation, between the people of Vietnam and the people of Ireland.

By adopting a new set of transformational Global Goals, the nations of the world have given themselves little less than the task of crafting a reflective and holistic vision for development and social progress. Your generation has a historic opportunity to lay the foundations of a new model for human flourishing and social harmony – one that is shared between all those who dwell on this planet, and one that is shared, too, between this generation and those yet to come. Let us commit, today, together, to make this promise thrive and bloom.

My hope for this new century, and I know your hope, is that we will manage, together, to build a cooperative, caring and non-exploitative civilisation, informed by the best of the traditions and institutions of the nations of the world, but also by the diversity of our collective experiences and memories – including those that will inevitably recall old wounds, failures and opportunities lost, but also visions revived and futures you will imagine and bring to be.

And, the people of Vietnam will be, I am certain, so much stronger for the enormity of what you have been asked to forgive, but which you must never be asked to forget. You are an indomitable people, capable of treating all of the challenges I have mentioned. My hope is that we will, together, recognise and give solid institutional foundations to the solidarity that binds us together as human beings, enjoy and cherish the responsibility we share for our common planet and vindicate the dignity of all those who dwell on it.

We are all but migrants in time and space – transient travellers who must do our best to pass on to the next generations, a hospitable ground, on which they can flourish – let us try to do it together.

Go raibh míle maith agaibh go léir.