Speech at the New Year’s Greetings to the Diplomatic Corps

Áras an Uachtaráin, Tuesday, 29th January, 2019

A Oirircis, A Dhéin an Chóir Thaidhleoireachta,

A Oirirceasa,

A Aire,

A Aíonna Uile, agus a Dhaoine Óga ach go háirithe,

Cuireann sé áthas orm agus ar mo bhean chéile, Saidhbhín, céad míle fáilte a fhearadh romhaibh go léir go hÁras an Uachtaráin.

Your Excellency, Dean of the Diplomatic Corps,

Excellencies,

Minister,

Distinguished guests,

It is my great pleasure to welcome you and your families to Áras an Uachtaráin. May I wish each and every one of you, and, through you and your Heads of State, all the citizens of your countries for 2019 a year of renewed international co-operation and progress in our national and shared endeavours.

May I thank His Excellency, the Most Reverend Archbishop Okolo, Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, for his warm words and good wishes for the New Year.

This year, I have decided to break with tradition and to commence my speech with a toast.

So, may I propose a toast to the Heads of State here represented.

Excellencies,

Distinguished guests,

Five months ago, I had the honour of welcoming Pope Francis to Áras an Uachtaráin. At this dangerous moment in the history of our planet and our people, Pope Francis has been a consistent and forceful voice for peace and justice, offering intellectual and moral leadership to a world desperately in need of both. It was a pleasure to continue our previous discussions, on the importance of meaningful pursuit of just international order, social cohesion, solidarity and human rights which must be at the heart of our political and personal responses to the current challenges facing global communities. I so share his belief that we must all work to resist a culture of indifference to these challenges.

Dear friends,

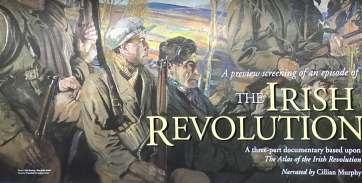

I was honoured that so many of you attended the centenary of the inaugural meeting of the First Dáil Éireann at the Mansion House which was celebrated last week. That supreme act of self-determination in January 1919 was, for us, a vital step in our long journey towards national freedom.

It asserted the right to national self-determination and invoked the ideals of popular sovereignty and democratic self-government, the First Dáil Éireann sought to take its place in the new world.

One of the first acts of the Dáil was to send envoys to advocate for Ireland at the Paris Peace Conference which was meeting to formally end the ceasefire declared by the Armistice of 1918.

Many members of the First Dáil had invested their hopes in the Peace Conference as the means to peaceably achieve an independent Irish republic. Despite the looming presence of the British at the Conference, this was no idle fantasy, for Ireland had long found sympathy, solidarity and support in France and Italy, whether from French Jacobins or Mazzini and the republicans of Young Italy. Above all, the Irish delegation looked to President Wilson – and beyond him to Irish-America – for support.

The year 1919 then marks not only the commencement of our War of Independence but announces the beginning of Irish diplomacy in new circumstances by the new Irish independent State. That first Irish delegation was led by a Dáil deputy who would go on to become our second President, Seán T. O’Kelly. He, like his comrades, believed that Ireland should have an independent foreign policy, one that reflected the values and aspirations of the Irish people.

Those values were encapsulated in one of the documents ratified by the First Dáil, the ‘Message to the Free Nations of the World’.

Last Monday, you will have heard it spoken in Irish and English – the first and second languages of the republic – and French, the language of international diplomacy. Its words still echo through the years, not only as a demand to enter the family of nations as an equal, but as the founding document of an independent Irish diplomacy. The Message stated that Ireland,

‘believes in freedom and justice as the fundamental principles of international law, because she believes in a frank co-operation between the peoples for equal rights against the vested privileges of ancient tyrannies, because the permanent peace of Europe can never be secured by perpetuating military dominion for the profit of empire but only by establishing the control of government in every land upon the basis of the free will of a free people’.

Thus from the very beginning, the vision of the new republic was outward looking, not only because it was vital to achieve international recognition for a fragile, emerging state, but because the members of the First Dáil recognised that – as a small nation – Ireland could not stand back from the world but needed to fully engage with other countries and emerging international institutions to ensure its survival and viability as an independent people.

The Irish envoys were not the only advocates in Paris. They were part of a wider international effort that sought to assert national self-determination. Although they were refused formal recognition, Sean T. O’Kelly and his colleagues continued to work with representatives of other nations who sought to assert their right to freedom and self-determination.

The Irish delegates cooperated with the Egyptian delegate to the Versailles peace conference, Zaghlul Pasha, in trying to influence the proceedings. Another young revolutionary also in Paris that spring, Ho Chi Minh, petitioned the conference for the rights of the Vietnamese people expressing his hope for, in his words, ‘the prospect of an era of right and justice’, although their aspirations would not be realised until much later in the century. The freedoms allowed for discussion were limited to the realms of defeated empires. Freedom for peoples caught within the maw of the victors was not for discussion.

Unfortunately, like their international colleagues, the Irish envoys received a cold reception in Paris. Although the imperialist impulse had been discredited by the carnage of the First World War, its instincts re-emerged in Paris as the great powers re-asserted again that very mode of statecraft which had failed in 1914. The opportunity presented by the vision embodied in the creation of the League of Nations was squandered as the great powers sought to carve up the remnants of the old empires that had disintegrated in the aftermath of the First World War. The results of that act of folly would cause the world to slip into an even larger catastrophe 20 years later.

There is a lesson in that failure: a warning as to what happens when nations neglect to make international mechanisms work effectively or allow themselves to become detached from them. The result for those following such an illusion is not necessarily greater freedom of nation action, but rather the risk of a journey down the darker paths of isolationism, an aggressive and inward-looking form of nationalism and for all nations and their peoples, has the consequence of an escalation of global tensions.

In taking the ‘Message to the Free Nations of the World’ to Paris, that Irish delegation of one hundred years ago pursued a different vision of world order, one founded on international co-operation based on the fundamental principles of democratic consent and sovereign equality. Those values would continue to inspire Ireland’s foreign policy and diplomatic practice.

In that spirit and pursuing these values, Ireland is seeking to become an elected member of the United Nations Security Council in 2021. We are seeking this role because we believe that not only is it important for the voices of smaller United Nations member states to be heard in Security Council debates, but because we accept our profound obligation as a member of the community of nations to contribute to international peace and security.

Ireland has consistently sought to live up to that obligation through our support for international peace, justice and the rule of law. This is given practical meaning through our commitment to disarmament, UN Peacekeeping and our Overseas Development Assistance Programme.

Ireland’s bid for membership of the United Nations Security Council is also part of a wider strategy to deepen our global engagement, and to enhance its effectiveness, through the Global Ireland initiative. I welcome the Government’s commitment to build new partnerships with countries where we do not have official representation, and to deepen our existing partnerships by strengthening and expanding our network of embassies.

Dear Friends,

There is, for all of us, a worrying sense of the shadows gathering in the wider international context and in relations between states. The world faces unprecedented challenges. Some states are resiling from commitments solemnly made and recorded, in some cases they are seeking to return to the old politics of perceived bilateral advantage which had such bleak consequences in the last century.

The diagnosis of the problem we all face is, after all, reasonably clear, even if many states don’t agree on the remedy.

The increasingly interlinked nature of the problems at global level is obvious: climate change, inequality, poverty and deprivation, the impact of new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence on employment, migration and population flows, trans-national crime and terrorism, and the need for a fair global trading system that delivers prosperity for all people.

These problems are what the late UN Secretary General Kofi Annan described as “problems without passports” because they affect us all and show scant regard for the limitations of national borders.

When I spoke to the diplomatic corps in 2016 just three years ago we were celebrating two great achievements – the UN sponsored agreements in New York on Sustainable Development and the Climate Change Agreement in Paris. It was more than a moment for optimism. It offered a great co-operative and necessary project to the world.

In his address to the UN General Assembly in 2018, Secretary General Antonio Guterres highlighted how the world is suffering from a bad case of “Trust Deficit Disorder”, in which people feel troubled and insecure and are losing faith in their own political institutions and the rules-based global order. He recalled how co-operation between countries is less certain, and the divisions in the UN Security Council have become starker.

While multilateralism is sometimes criticised as overly complex and incapable of delivering, the Secretary General also reminded us of the achievements of multilateralism – in fostering peace, defending human rights and driving economic and social progress for men and women everywhere.

It is essential surely that we strive to engage our peoples in achieving projects that are new ones of survival itself in biodiversity and planetary terms. We are asked for authenticity in our words and actions.

For concourse between nations is not only a matter of diplomatic links purely at the level of the state but is so richly expressed in international networks of solidarity and support.

There is no better example of this than the story of another Irish delegation, too often unheralded, who did achieve a measure of success in promoting Ireland’s cause in 1919. In February of that year, the Irish trade union and labour movement nominated Thomas Johnson and Cathal O’Shannon to attend a meeting in Berne of the social democratic parties of Europe. The delegates assembled in Switzerland sought to re-establish the Second International sundered by the First World War.

That conference, unlike the Versailles experience, recognised Thomas Johnson and Cathal O’Shannon as representatives of the Irish labour movement, distinct from that of Britain.

Though they were formally speaking for Ireland, the two men were at pains to emphasise that they were bringing a message from their comrades from Egypt, Indochina and India who could not attend. They demanded self-determination for all those countries based on a national plebiscite on whether to leave their respective empires.

The re-constituted Second International would go on, in April of 1919, to unanimously demand that ‘the principle of free and absolute self-determination shall be applied immediately in the case of Ireland’. This perhaps neglected incident in our history emphasises the emergence of the international trade union and labour movement as a force for peace and justice in the world in the past century. It is an influence that abides today.

As the International Labour Organisation so often seeks to remind the world, there can be no universal peace without social justice.

Is it not the case however, in our times, one might ask that this aspiration, while given rhetorical support, is contradicted again and again by the failure to allow connections of social responsibility to come into being, flourish or be sustained between capital, labour, economy, ecology and ethics? The International Labour Organisation faces a constant struggle against its marginalisation in conditions of a growing unaccountable sphere in a financialised global form of borderless capital.

As a planet, and as a family of nations, we face new and neglected challenges: persistent inequality in wealth, income and power; poverty; environmental degradation and a loss of biodiversity; and above all, the catastrophic consequences of climate change.

In other years we have all agreed that these are challenges that we can only meet together, and that we can only confront if we are willing to re-examine and change some of our fundamental assumption and yet we are not offering a response our planet and our peoples need and must be encouraged and assisted to seek. Is Pope Francis’ description of ‘a culture of indifference’ not far from a description of where we are in our private existence, and in so many places, in public life?

Last October, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a report on the possibility of the planet meeting the pledge we made to our peoples and to each other at Paris in 2015. It makes for stark reading, for it demonstrates that we have a very short time frame – the headline figure is 12 years - to act if we are to keep the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The level of climate change mitigation required to achieve that goal demands nothing less than revolutions in power generation, in our food production and consumption systems, in our land use, in our transport, planning and infrastructure, and in industry.

As expensive as all this might be for some, we must recognise that the cost of climate adaptation grows correspondingly higher with each temperature increase.

If we are not to abandon vast swathes of humanity to repeated and deepening tragedies of climate change we must act and now and act quickly. It is now becoming clearer that the formal pledge that we made at Paris – of a 2 degrees Celsius increase in temperature above pre-industrial levels – will be insufficient to save many nations from devastation.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Climate Accords represent the two most remarkable successes for international co-operation and diplomacy in this decade. Together, they provided the means by which we shall measure our success and failure in this century. They are demonstrations of the possibility of global solidarity in the face of overwhelming challenges. We cannot afford to let them be weakened, even absconded. We have to accept too that beyond our generations’ welfare this is an issue of inter-generational justice.

The outcome of the Katowice Climate Change Conference gives some further cause for hope, insofar as nations have agreed on the methodologies by which they will evaluate their efforts under the Paris Accord. However, some nations are now turning from the commitments that they have made, instead affecting a wilful indifference to the overwhelming scientific evidence.

I am conscious that we in Ireland must do more, far more, in our mitigation efforts, and to do so at a far greater pace than we have hitherto. As the representative of the UN Secretary General said at Katowice, we must all demonstrate determined ambition: ambition in mitigation, adaptation, finance, technological change, and innovation.

Dear Friends,

While we might even agree on the wider global challenge of what we face and the interlinked nature of new and existing challenges – climate change, environmental degradation, an unequal global trading system, the overweening power of multinational corporations - there is no consensus regarding the underlying cause of those symptoms, nor the proposed treatment.

That falls to the realm of politics and will be a matter for all our citizens upon which to deliberate and debate. They need the pluralist scholarship that can offer new paths to a sustainable, globally just future. They need options that are ethical, ideologically responsible. They need what was of assistance in great crises of the past, an unbiased, informed media, free of monopoly, genuinely open to critical thought. They need institutions of education free of the dominance of extreme market forces.

As we do so, it is vital that we maintain our commitment to the international institutions at the heart of our global political community.

Multilateralism is sometimes criticised as overly complex and incapable of producing solutions, but, as Secretary General Guterres reminded us in address to the General Assembly last year, it has also succeeded in fostering peace, defending human rights, and propelling economic social development across our planet.

Dear Friends,

The global challenge of poverty, deprivation and inequality remains a priority for Irish foreign policy. I am pleased that the Government will shortly publish a new White Paper on International Development, which will re-affirm that Ireland will continue to seek to build a fairer world. It will re-state Ireland’s commitment to meeting the United Nations target of 0.7% of Gross National Income in overseas development assistance.

The new White Paper will, I hope, clearly establish that we must all move on from these simplistic unilinear models of development and engage with a diversity of sources of wisdom, scholarship and research in building alternatives that will work. The new White Paper will stress the urgent need to protect multilateralism, the role of the State in new circumstances of challenges and technology, the unique role of civil society, and the important task of preventing the erosion of globally-agreed norms and principles.

Ireland’s commitment to global justice and the rule of international law is not limited to our vital development work. During my Presidency, I have had the opportunity to witness the dedicated and professional manner in which Irish peacekeepers contribute to Ireland’s reputation overseas and the maintenance of international peace and security. Since 1958, the Defence Forces have maintained a continuous presence on peace support operations.

It is a remarkable record, and we can be justifiably proud of the courage, determination and professionalism of the members of the Irish defence forces who are deployed on operations in the Middle East, in Africa, or on missions in the Mediterranean where every day they help save the lives of those fleeing conflict or persecution.

Dear Friends,

The European Union remains at the heart of Ireland’s foreign policy. Since our accession in 1973, it has been fundamental to our national development.

That bridge to the wider world has expanded the opportunities available to all Irish people, and the European Union has very often been the source of new rights – the right to equal pay irrespective of gender, the right to equal treatment, expanded labour rights.

Yet, our European Union is now challenged by the erosion of, and, indeed in some quarters outright challenges of, some of the fundamental principles and aims that underpin our Union. Social justice and social protection, solidarity between generations, economic and social cohesion, and solidarity between Member States are all fracturing, as Member States and the Union institutions themselves struggle to uphold these values. And for the first time, a Member State of the European Union has decided to leave, an eventuality thought once thought remote, even fanciful.

The decision of the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, and particularly the intensification of events in Westminster in recent months, has perhaps to some extent deflected attention from the necessity of our own debate here in Ireland regarding the future of our European Union. That debate is all the more important now as we face into very important European parliamentary elections this year, elections that may prove a watershed moment in the life of the Union.

Last January, I made my own contribution to our national debate regarding the future of Europe. I posed a number of questions which I thought were critical to any envisioned or planned institutional change: can the macro-economic framework of the European Union sanction and protect a diversity of models, both in terms of welfare states and alternative economic models? Can the formulation of monetary policy be accommodative of such difference? Can the rules of the internal market yield where they can and surrender when they must to the demands of labour?

I am not sure that we are any closer to resolving the institutional problems at the heart of our Union, or what has become a clash between our fundamental values and principles – such as solidarity and a commitment to social justice – and parts of what might be called the ‘Economic Constitution’ of the Union which has emerged and has been embedded in the Treaties.

The spokespersons for the macro-economic institutions of the Union too often seem to be holding the assumption that economic and fiscal complexity is beyond the comprehension of our European citizens.

Such an approach is delivering a negativity to the European street, continuing to divide rather than unite, leading to discord between Member States and the institutions, all of which serves only to frustrate citizens who look to the Union to vindicate those values and objectives for which the Union itself was brought into existence.

The voices of the European street call for a Union pursuing equality, and offering prospects for a decent life, for cohesion, not the continuance and projected performance of a patchwork of inequality defined by the economic strength of the few and the accepted weakness of the others.

There are opportunities that have been missed by a concentration on the impact of a global financialised economy, at the cost of social cohesion. One of the most innovative features of the Maastricht Treaty was the establishment of a Committee of the Regions, which consists of the elected representatives of regional and local governments.

It is one of the, perhaps neglected, inheritances of Jacques Delors’ expansive vision for the Union.

We should, I suggest, raise again the important of regional policy within the European Union, not only in terms of sub-national governments, but in terms of regions and nations with shared challenges.

Is it possible to provide regions with the benefits of the Union while recognising diversity in terms of economic and social structure? For example, can ‘subsidiarity’ not be defined positively rather than negatively. Yes, it is possible and, in doing so, we would be acknowledging in a policy sense demographic, social, economic differences while still living within the treaties. Our solutions are in the realm of politics, a politics of engagement.

If we need a recovery of regionalism, and of regional planning, then we surely also need to recover, for our shared future, a discourse on the role of the State in allocating investment and planning for the future. Why are we not having a debate on the role of the State in appropriate and accountable partnerships as we face new shared challenges in utterly changed circumstances?

In previous speeches, I have been frank in expressing my regret at the decision of the British people in 2016 to leave the European Union. However, I wish to reiterate today that however the challenge of Brexit is resolved it will be more essential than ever in the years ahead to sustain and build upon the deep friendships which have grown between Britain and Ireland, and within our Island.

At this time, I want to particularly emphasise a key point regarding the Brexit debate. In the Brexit negotiations the core aim of the Irish Government in regard to relationships on these islands, an aim which I share, is to preserve the provisions and principles of the Good Friday Agreement. This is not a straightforward task given the Agreement was formulated upon the assumption of continuing European Union membership across these islands.

As many of you who have crossed the border in your role will know, it is no longer a physical barrier between the people of North and South. The removal of the border infrastructure, and the re-opening of border roads, has helped open up a space where people and commerce can circulate freely, and the possibilities of co-operation between the two parts of the island can be fully realised. It is critical that this remains the case, and that the barriers of the past which blocked those possibilities are not re-erected. The aim of the Government has always been, as the Ulster poet John Hewitt put it, to ensure “that each may grasp his neighbour’s hand as friend”.

The Good Friday Agreement represents a remarkable and sustained achievement of peace-making and reconciliation. The Agreement demonstrates that a shared commitment to universal human rights – to equal treatment, to parity of esteem – can facilitate the creation and enrichment of shared space, one capable of accommodating different aspirations, one in which it is possible to imagine and shape a future of hope and possibility.

As we move forward in all the strands of our relationships – North and South, East and West and in a wider European context – we must defend the achievements of the Good Friday Agreement.

In that context, we should remember also the social and economic dimensions of the agreement. They can be a powerful source of social cohesion and sustainable economic life.

A durable settlement must encompass the right to decent work, to social protection, to security from fear of insufficient provision in health, housing and education, to ensure that there is no return to the despair and alienation which caused conflict in the past.

Dear Friends,

A century ago, the world had to deal with the consequences of “classical great power” diplomacy – the diplomacy of self-interest and of imperialism – which led to what the poet Thomas Hardy described as ‘the breaking of nations’. In our time, we have also witnessed the brutal consequences of the failure of diplomacy in Syria and Yemen, and the collapse into chaos and violence of those countries.

In Yemen, the UN Secretary General has warned the world that 22 million Yemenis are in desperate need of humanitarian aid and protection. We have seen and read the bleak reports by the distinguished Irish journalists Orla Guerin of the BBC and Declan Walsh of the New York Times. The UN needs our sustained support as it tries to bring an end to the conflict, and to provide the necessary humanitarian relief to alleviate suffering, famine and deprivation.

Ireland has also provided ongoing support to relieve the terrible consequences of the conflict in Syria.

Our humanitarian aid has exceeded 100 million euros both as a practical measure of vital assistance, and as an expression of our solidarity with the victims of conflict. We have welcomed displaced Syrian refugees to Ireland, and it has been heartening to see how the generosity of the Irish people has been expressed in the warmth with which those fleeing conflict have been greeted as new neighbours.

At the same time, a sustainable political resolution is the only way to ensure a lasting end to the violence and suffering in Syria. For that reason, Ireland continues to support UN led efforts to end the conflict in Syria.

The Global Compact on Migration, endorsed in December 2018, represents welcome progress in dealing with the challenges presented by the unprecedented level of migration globally. We must always place at the heart of our efforts to respond to migration not only the human dignity that is the entitlement of us all, even more so when faced with conflict or suffering, but how our commitment to a shared planet is tested by the nature of our reactions. We must not turn our backs or shut our doors on people when they are at their most vulnerable. We are rather afforded an opportunity for fulfilment, to experience a version of the best of assertions.

Dear Friends,

In your role as diplomats and representatives of your country, I know that you have an awareness of a profound responsibility to ensure that your leaders and legislators have the information, both truthful and accurate, that is critical to making the right decisions to address the global challenges we all face.

It falls on our political leaders to take action, but as diplomats your responsibility is to help interpret and make sense of the wider global context and not from a narrow sharing of colleagues views, however valuable they may be, political leaders must, for all our sakes, and for the sake of future generations, take decisions rooted in a sound understanding of the realities of the world and most importantly, the informed citizen of the global street.

That is not always an easy task, or one that is without professional or personal risk. In his autobiographical meditation on the political crises of the 1930s, “Autumn Journal”, the Belfast poet Louis MacNeice acknowledges the difficulty we all face in facing up honestly to the complexities of a rapidly changing and dynamic world. MacNeice reminds us that:

None of our hearts are pure, we always have mixed motives.

Are self deceivers, but the worst of all

Deceits is to murmur 'Lord, I am not worthy'

And, lying easy, turn your face to the wall.

We are all summoned not to turn away, but to face courageously into the light of the future. We live in an age of rapid change that demands from all of us great qualities of energy, determination, idealism and optimism.

In 2019, we must keep faith with those ideals not just to imagine a better world; so that we can build upon the positive legacies of 1919 exemplified by the idealism of our diplomatic predecessors, as they sought to assert the universal rights to freedom and self-determination of all peoples. We, in our time, must guard against the mistakes of isolationism and a narrowly defined national interest that ignores our mutual obligations as inhabitants of a shared and fragile planet.

Go raibh míle maith agaibh go léir.