Address to the World Food Forum Grand Opening 2025

FAO Headquarters, Rome, Italy (via video from Dublin) 13 October, 2025

Excellencies,

Distinguished Guests,

Dear friends,

A chairde uilig,

May I say how much I deeply appreciate the honour of being asked to address this year’s opening ceremony of the World Food Forum, and of joining with you in marking 80 years of the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s work at the United Nations.

I had the privilege of delivering two addresses on food security at the World Food Forum in 2023. I was pleased to have the opportunity to expand in Rome on the concepts which I had previously outlined when speaking in Senegal earlier that year of the need for a new approach that is ecologically responsive and sustainable. One that breaks dependency.

I later developed this further when speaking at the United Nations in New York last year, and again while delivering the Kofi Annan lecture for the African Development Bank.

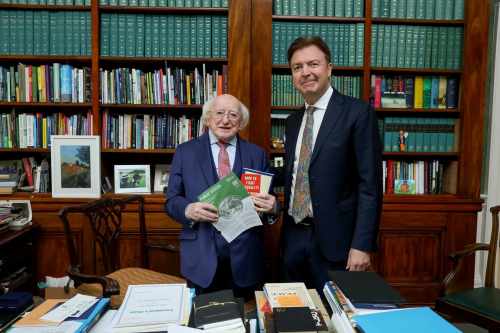

May I once again express my deepest thanks for the honour which the FAO and Director-General QU Dongyu bestowed on me with the award of the Agricola Medal at a ceremony in Dublin last year.

Food security, and the achievement of food security, are themes which I am anxious to continue working on after I complete my term as President of Ireland in a few weeks’ time.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation, I believe, can lead the new approach we need.

FAO was founded 80 years ago with a vision to end hunger and to advance food security for all.

The reaction to my speeches, in Africa in particular, a continent of 1.5 billion people which, by 2030, is expected to constitute 42 percent of the world’s youth population, has convinced me that the committed young people of today can achieve, where previous generations did not, and succeed in eliminating global hunger and global poverty.

In speaking to you today, I wish to emphasise one point above all others – that this goal will not be achieved by simply adjusting existing models of food production and distribution.

Instead, a radical change is necessary. One based on the breaking of food dependence, achieving food sovereignty, and of doing so within conditions of ecological responsibility and justice.

All of this is achievable. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Declaration of 2015 were moments of great hope which reminded us of what is possible.

However, the reluctance to live up to the promises which were made ten years ago and retreat from what was committed are having a devastating effect.

What an appalling statistic it is that an estimated 673 million people are today living in conditions of hunger.

Nine out of the ten most climate-vulnerable countries in the world are in sub-Saharan Africa, while the 20 countries most affected by climate change between them account for just 0.55 percent of global emissions.

According to the 2025 Global Hunger Index, conflict remains the most destructive force driving hunger across the planet, fuelling 20 food crises affecting 140 million people in the past year, while wars in Gaza and Sudan illustrate how conflict devastates lives and livelihoods.

With humanitarian assistance being so sharply cut, as military spending surges, we have an inversion of priorities that undermines the global hunger response.

Elsewhere, rising levels of obesity and widespread food waste point to a system out of balance—where abundance and absence coexist, often side by side.

In so many ways, we are wrestling with the consequences of a globalisation ‘from above’, led by powerful forces of oligarchy and concentration of power without transparency, without consideration as to social justice or ecological consequences.

In addressing food security, we must now move past previous reactive emergency humanitarian responses, necessary and important though they are, and undertake the urgent task of tackling the underlying repeating structural causes of hunger.

The issues of ownership of seeds, fertilisers, tools of production and their distribution, food speculation in crops, obstacles to the migration of science and technological innovations, questions as to the lending policies of the financial institutions – all of these issues cannot continue to be ignored, and must be pushed to the fore in the discourse.

Fundamentally, there are two competing models of food security vying for adoption: one based on industrial agriculture and re-positioning in global supply chains, the other, stressing the agency of smallholders, focused on the achievement of the United Nations 2030 Agenda.

I am delighted that the Food and Agriculture Organisatio is making a particular appeal to young people, and I urge them to seize the opportunity in their different countries to press for the new model which I have described when receiving the Agricola Medal as a ‘globalisation from below’ – one which can be achieved by the upskilling and empowering of citizens. It is something which the FAO achieved in the 1950s with its response to the Asian food crisis.

Ending hunger, through a transformed food system, has the ability to restore ethical purpose to humanity. It is a basis for seeing beyond narrow interests and immediate short term horizons, and of embracing our shared responsibility – steering future generations towards a future of sufficiency: A better life, sustained by a better environment, nurturing better food and nutrition.

I believe that there are some basic issues that surely cannot continue to be ignored, issues relating to gender, land ownership, commodity choices, the external purchase of land and, most fundamentally, the need to redefine ‘development’ itself as a concept of sufficiency, sensitive to contemporary conditions, inclusive of the best aspirations for life, enabling for the fullest participation both in life and in government, all of this achieved with ethics, and bearing responsibility for future generations.

It will be of enormous benefit to democracy itself to seek to achieve food security within a model of sufficiency with what is traded coming from what is accepted as a surplus.

Achieving food security is a building block for democracy and participation. When combined with universal basic services it can in fact introduce, defend and extend democracy.

In being people-led, such a model, respectful of diverse indigenous cultures, will make a significant contribution to participation and citizenship, and be a source of the leadership needed to create a sustainable shared future.

Dear Friends, change is possible.

I strongly support the Democracia Siempre initiative of President Lula and President Boric, and the Global Alliance of President Lula and others on the elimination of global hunger and global poverty. The upcoming COP in Belém and South Africa’s Presidency of the G20 are so important moments in this work.

It is clear that today, just as in 1945, hunger has no respect for borders and no country can overcome it alone.

Our best strategy for lifting millions of people out of food insecurity, hunger and famine is to act together, urgently and with solidarity, with multilateral institutions like the Food and Agriculture Organisation leading the way.

We are challenged to embark on a new beginning.

At this year’s World Food Forum, I urge you to work towards one that is inclusive, life-affirming and celebratory of diversity, one that can work in a variety of settings, including Africa, upon which so much of our hope for the future rests, one that adequately responds to climate change and the needs of sustainability, one that offers best possible prospects for avoiding unnecessary conflict and achieving peace within and between peoples.

You must succeed in the name of all humanity.

Thank you. Buíochas.