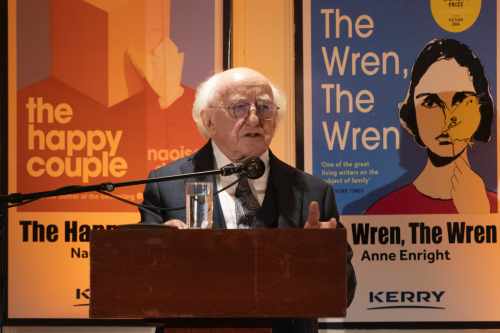

Speech by President Higgins Marking the Centenary of the Courts of Justice Act 1924

Áras an Uachtaráin, Tuesday, 28th May, 2024

Chief Justice,

Presidents of Supreme Courts,

Taoiseach and Distinguished Guests,

A cháirde,

Is mian liom fíor-chaoin fáilte a fhearadh róimhaigh uilig go Áras an Uachtaráin ag an ócáid shuntasach seo agus muid ag ceiliúradh 100 bliain ó Acht na gCúirteanna Breithiúnais 1924 a achtú.

[May I say how pleased I am to welcome all of you here today to Áras an Uachtaráin on this special occasion as we mark 100 years since the enactment of the Courts of Justice Act 1924.]

May I pay a particular welcome to Síofra O’Leary,

President of the European Court of Human Rights who joins us today. May I also offer a warm welcome to the senior representatives from eleven countries who have travelled to Ireland this week.

In recent years we have been marking the decade of centenaries – those formative years that commenced perhaps with the 1913 Dublin Lockout and culminated in the establishment of the Irish Free State. However, what happened in the few years after 1922, which include the legislative changes of the Free State government in those early years, were formative actions that would have an enduring legacy.

In a letter to the Executive Council members of the Irish Free State in January 1923, President WT Cosgrave wrote,

“there is nothing more prized among our newly won liberties than the liberty to construct a system of judiciary and an administration of law and justice according to the dictates of our own needs and after a pattern of our own designing.”

There was however, a context to this view.

A particular challenge arose in relation to the division of domain lands. The 1923 Land Act had come after a number of earlier acts which had their beginning in the 1880’s which had turned tenants into peasant proprietors. It had released a hunger for land. After the 1923 Act and the acceptance of the majority report of the 1924 Commission on Agriculture, the grazier-led cattle economy was privileged. This was interpreted widely as abandonment of the aim “the land for the landless”. Land agitation was widespread and a special force was established to deal with it - the Special Infantry Corps. Those released in late 1923 or 1924 from incarceration as Anti-Treaty prisoners would regularly have their names given to the special anti-land agitation group. Many of these were forced to leave their native parishes, and a considerable number emigrated, as did agricultural labourers, as tillage gave way to cattle.

A particular challenge arose in relation to the division of domain lands. Within months of taking office, Cosgrave established a Judiciary Committee, chaired by former Lord Chancellor Lord Glenavy, appointed to advise the Cabinet of the Free State on the establishment of a new courts system, one that would supersede the Dáil Courts, or Republican Courts, the judicial branch of government of the Irish Republic which had unilaterally declared independence in 1919 and which had been established by a decree of the First Dáil on 29th June 1920.

The Dáil Courts were an important element of the Irish Republic’s policy of undermining British rule in Ireland, establishing as they did a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. The seizing of power by the people, taking over the administration of law and order in their own communities and turning their backs on the enforced British judicial system, made international news, as Mary Kotsonouris has noted in her book, Retreat from Revolution: The Dáil Courts 1920-24 .

Small tribunals adjudicated in local disputes about land, the local Volunteer companies abducted and punished thieves and petty criminals, directed public order at race meetings and fair days, and in some parts of the country burnt down the existing court houses.

President Cosgrave’s appointment of Glenavy as Judiciary Committee Chairman was an exercise in bridge-building. Lord Glenavy was an establishment figure under the old regime, a staunch Unionist who had served as MP for various Dublin constituencies and a leading member of the Masonic Order, so it was perhaps surprising. On the other hand, he had accumulated considerable legal experience having been successively Attorney General, Lord Chief Justice and finally Lord Chancellor of Ireland, immediately before independence. He certainly found favour with the Free State government which also appointed him to the Senate of which he became the first Chairman.

Incidentally, we can probably thank him, or blame him, depending on your perspective, for having saved the traditional wig and gown worn by judges and barristers . Hugh Kennedy (then Attorney General and later Chief Justice) wanted to replace this garb with a new uniform, and by all accounts a highly colourful one, modelled on what he believed Irish Brehon judges would have worn centuries earlier. Glenavy ridiculed this proposal, saying:

“Remember, this is a thing that can be altered and re-altered by each successive Minister for Home Affairs. The present Minister for Home Affairs might prefer a kilt. His successor might be a sporting man, and he might prefer a jockey’s costume. The next successor might have clerical tendencies, and he might prefer to see the judges robed in clerical costume. Where is this thing to end?”

The Glenavy committee produced a report in May 1923, with detailed recommendations for the establishment and operation of the District, Circuit, High and Supreme Courts. The Courts of Justice Bill 1923 was published in July and after much debate, the Courts of Justice Act 1924 was signed into law and commenced in the summer of 1924.

Today we mark this important milestone in Ireland’s history. The Act is one of the most significant pieces of legislation passed in the Free State, establishing as it did the basic structure of our courts system, which has endured for a century, with only the addition the Court of Appeal in 2014 and the Special Criminal Court, the first of which was established in 1972 and the second in operation since 2016.

The 1924 Act was wide-ranging, seeing District Courts replacing the Court of Petty Sessions and the Justice of the Peace. The Justices of the District Court were professional judges and had jurisdiction over minor civil and criminal matters. The Circuit Court had jurisdiction in more serious civil and criminal matters.

On the criminal side, the most serious offences, such as murder, were reserved to the High Court. A Court of Criminal Appeal to hear appeals from the Circuit and High Courts was also established. Provision was made for a further right of appeal to the Supreme Court on a point of law of exceptional public importance. The Supreme Court was created as the final court of appeal, to be presided over by the Chief Justice.

Prior to English rule, Ireland had its own indigenous system of law dating back to Celtic times, which survived until the 17th century when it was finally replaced by the English common law.

This native system of law, known as the Brehon law, developed from customs which had been passed down orally from one generation to the next. Indeed it was the 7th century before laws were written down for the first time.

Brehon law was administered by Brehons (or brithem), the successors to Celtic druids and, while similar to judges, their role was closer to that of arbitrators, tasked with preserving and interpreting the law rather than expanding it.

In many respects Brehon law was enlightened and progressive by today’s standards. It recognised divorce and equal rights between the genders and also showed concern for ecology.

In criminal law, offences and penalties were defined in great detail. Restitution rather than punishment was prescribed for wrongdoing, this being a feature shared with many indigenous systems including those in Africa which have been widely studied. Cases of homicide or bodily injury were punishable by means of the Éraic fine, a form of tribute paid in reparation for murder or other major crimes, some of the exact amount determined by a scale. Capital punishment was not among the range of penalties available to the Brehons. Indeed the absence of either a court system or a police force suggests that people had strong respect for the law.

Seeking to extend its influence, English authorities sought to reassert the supremacy of their Parliament and of English law over any Irish Parliament or Irish legislation by enacting the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366, followed by the enactment of two statutes at a Parliament held in Drogheda in 1494, together known as Poyning’s Law, which provided that the King’s Privy Council must give prior assent to the assembly and legislation of an Irish Parliament, and that all laws passed in England applied to Ireland.

By the 16th century, English law was confined to an area known as the Pale, made up of Dublin and the east coast, beyond which, Brehon law continued to be applied.

It was not until the reign of King Henry VIII, some decades later, that English law extended further when the King implemented a scheme of ‘surrender and re-grant’ of the land held by native noble families, which brought them within the feudal system of land tenure.

English law gained a further foothold following the defeat of Irish forces at Kinsale which was followed by the ‘Flight of the Earls’ from Ulster in 1607 and the consequent Plantation which saw the land being granted to Scottish and English settlers. The Flight of the Earls had an added significance in that it removed the Brehons’ remaining source of patronage, and the end of the Brehon Law’s authority was signalled by the Proclamation of King James I in 1603, which resulted in Ireland being subsequently divided into counties, a legacy of doubtful value in administrative terms right up to the present times. English law was now sought to be administered throughout the country.

The dominance of English law was consolidated by Oliver Cromwell’s military campaign (1649-1652), as a result of which many Irish landowners were forced from their holdings to resettle in Connaught. It was a forcible ejection of such for the purpose of satisfying the payment of wages to Cromwell’s soldiers. Brutal repression of Catholics in the form of the Penal Laws would later become a defining feature of the late 17th and into the 18th centuries, before a series of reforms were enacted, with calls for the repeal of the Act of Union gradually and continuously being amplified, with eventual separation from the Union coming via the passing of the Irish Free State (Constitution) Act in 1922. The period of oppression included exclusion on the basis of religion, proscription of the Irish language, its use punishable physically if used by children.

While every country has its own courts system – some of which are very different to the system we have in this country – they all aspire to the same aim: ensuring that justice is achieved and that the outcome of the case is fair and reasonable.

A fair and impartial judiciary and justice system is accepted as the bedrock of any functioning, democratic society.

Bunreacht na hÉireann, The Constitution of Ireland, has served us well over the past 87 years. While it did not provide the individual liberties and freedoms that everyone desired, it gave us the freedom, and the space, to achieve them. Today’s Constitution reflects how we have changed as a society and as a country.

In the past, Constitutions were sought to provide certainty and, when necessary, cast a cold judgement on people’s lives. Today, it recognises both the uncertainty and the possibilities of the changes that may be experienced in all our lives and has evolved to acknowledge the importance of respecting personal freedoms instead of limiting them.

One may well ask if there is any aspect of our republic more essential to its effectiveness and continuity than the independence of our nation’s courts and their ability to uphold the rule of law? It is, after all, our judiciary that has an enormous responsibility in being part of a system that seeks to ensure, not only that order is based on a legitimate and democratically sourced assent, is maintained in our nation, but also that the struggles in which the citizens of our country engage with each other—whether over law, ideas, politics, or social values—are resolved reasonably, and fairly.

The vindication of rights has required the transcendence of borders.

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights has affirmed that,

“recognition of the inherent dignity, and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family, is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world” .

The development of a regional system of human rights protections operating across Europe, as expressed in the subsequent European Convention on Human Rights, has played a crucial role in the development and awareness of human rights in Europe.

This Convention has ensured that people have basic needs recognised and sought to be met, that vulnerable groups are protected, that people can confront societal corruption, that freedom of speech and expression are encouraged, that freedom to practice religion and to love who they choose are safeguarded, that equal work opportunities are encouraged, that people have access to education, that the environment is protected and that governments can be held accountable.

Achievement of gender equality in terms of access to the highest positions in the administration of law is of such importance.

The reception for Women and the Law which I hosted in Áras an Uachtaráin in November 2021 recognised those first women called to the Bar. Great strides have, I am pleased to say, been made in terms of gender balance amongst the legal profession today, with many women in recent years holding the highest positions in our courts and legal institutions – individuals such as Catherine McGuinness, Susan Denham and Síofra O’Leary.

It may be appropriate to recall today the first Irish women called to the Bar on 1st November 1921 – Frances Kyle and Averil Deverell – who we remember as trailblazers, serving justice and making history.

Let us recall too those who provided an alternative to the prevailing orthodoxy of those early years in the new State, figures such as Thomas Johnson, a prolific legislator and committed parliamentarian who advocated for a peaceful alternative to the bloody conflicts that gripped the decades of our nation in its infancy. Again it was he and Mr. Buckley who wrote the Minority Report for the Commission on Agriculture.

As judges, you are the linchpins of the justice system, ensuring through your constitutional and judicial functions that the guiding principles of such hallowed documents as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and European Convention on Human Rights are upheld.

Law can, and it is important, be emancipatory, but only when our system of law is fair, maintains accountability and works to protect all citizens, especially the most vulnerable and marginalised members of society, can our nation truly prosper and flourish. This requires a diversity of educational life experience in our judiciary enabling them to garner and develop a trust among the citizenry.

May I thank all of you present today for the vital role that you play in ensuring that the courts of justice of our country uphold the rights of our citizens, that our democracy functions at the highest level and that our courts maintain their integrity and legitimacy in order to ensure that they protect the rights of all citizens.

Beir beannacht.